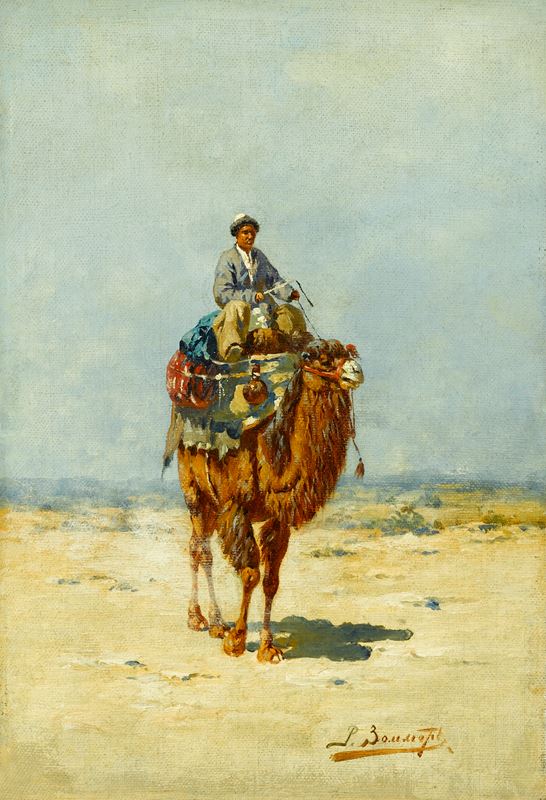

ichard Karlovich Zommer

(Munich 1866 - Russia 1939)

Kirghiz on a Camel

signed in Cyrillic (lower right)

oil on canvas laid on board

30 x 20.5 cm (11 x 8 in)

In Kirghiz on a Camel, Richard Karlovich Zommer cleverly immerses the viewer into the scene. Unlike many Orientalist painters, we do not feel like a foreigner or a detached observer in Zommer’s work, rather we become the Kirghiz rider, experiencing at first-hand this arid landscape and its unrelenting heat, the small shadow cast indicating the sun is near its highest point in the sky. Fully in command of his camel, the rider steadily encourages the animal on, his calm composure reminding us that, this journey is a routine part of his life.

For the Kirghiz, the camel was used both for the transport of goods and for their own personal use, such as transporting their house, or yurt, for which they would use two or three camels. The animals were fundamental to their nomadic lifestyle and their concept of ‘All I have, I carry with myself.’

The term Kirghiz comes from the legendary chief, Kirghiz, ninth in descent from Japheth. The Kirghiz are a large and widespread division of the Turkish family, of which there are two main branches, the Kara-Kirghiz of the uplands and the Kirghiz-Kazakhs of the steppe, which jointly occupy an area stretching westwards from Kulja to the lower Volga, and south from the head of the Ob towards the Pamir and the Turkoman country. Ethnically they are close to the Mongolians, while in language they are close to the Tatars.

Essentially nomads, the Kara-Kirghiz are mainly breeders of horses, and sheep as livestock, oxen for riding and, goats and camels as pack animals. The principle crops grown are wheat, rye, barley, oats and millet, from the last of which a coarse vodka or brandy is distilled. Trade is conducted chiefly by bartering, with cattle being taken by dealers from China, Turkestan and Russia, in exchange for manufactured goods.

The Kirghiz-Kazakhs, simply referred to as Kazakhs, are also predominately nomadic. Their dress consists of the chapan, a flowing robe of which one or two are worn in summer and several in the winter, fastened with a silk or leather girdle, in which are stuck a knife, tobacco pouch, seal and a few other trinkets. Broad silk or cloth pantaloons are often worn over the chapan, which is made of velvet, silk, cotton or felt, according to the rank of the wearer. Large black or red leather boots, with round white felt pointed caps, complete the costume. The domestic animals, daily pursuits and toils of the Kazakhs are in most respects similar to those of the Kara-Kirghiz. Some of the wealthy steppe nomads own as many as 20,000 large fat-tailed sheep. Goats are kept mainly as guides for these flocks, and their horses are hardy and capable of covering from 50 to 60 miles at a stretch. Amongst the Kazakhs a few are skilled in silver, copper and iron work, which are the chief arts besides skin dressing, wool spinning and dyeing, and carpet and felt weaving. However, trade mainly consists of exchanging their livestock for woven and other goods from Russia, China and Turkestan.

In Kirghiz on a Camel, Richard Karlovich Zommer cleverly immerses the viewer into the scene. Unlike many Orientalist painters, we do not feel like a foreigner or a detached observer in Zommer’s work, rather we become the Kirghiz rider, experiencing at first-hand this arid landscape and its unrelenting heat, the small shadow cast indicating the sun is near its highest point in the sky. Fully in command of his camel, the rider steadily encourages the animal on, his calm composure reminding us that, this journey is a routine part of his life.

For the Kirghiz, the camel was used both for the transport of goods and for their own personal use, such as transporting their house, or yurt, for which they would use two or three camels. The animals were fundamental to their nomadic lifestyle and their concept of ‘All I have, I carry with myself.’

The term Kirghiz comes from the legendary chief, Kirghiz, ninth in descent from Japheth. The Kirghiz are a large and widespread division of the Turkish family, of which there are two main branches, the Kara-Kirghiz of the uplands and the Kirghiz-Kazakhs of the steppe, which jointly occupy an area stretching westwards from Kulja to the lower Volga, and south from the head of the Ob towards the Pamir and the Turkoman country. Ethnically they are close to the Mongolians, while in language they are close to the Tatars.

Essentially nomads, the Kara-Kirghiz are mainly breeders of horses, and sheep as livestock, oxen for riding and, goats and camels as pack animals. The principle crops grown are wheat, rye, barley, oats and millet, from the last of which a coarse vodka or brandy is distilled. Trade is conducted chiefly by bartering, with cattle being taken by dealers from China, Turkestan and Russia, in exchange for manufactured goods.

The Kirghiz-Kazakhs, simply referred to as Kazakhs, are also predominately nomadic. Their dress consists of the chapan, a flowing robe of which one or two are worn in summer and several in the winter, fastened with a silk or leather girdle, in which are stuck a knife, tobacco pouch, seal and a few other trinkets. Broad silk or cloth pantaloons are often worn over the chapan, which is made of velvet, silk, cotton or felt, according to the rank of the wearer. Large black or red leather boots, with round white felt pointed caps, complete the costume. The domestic animals, daily pursuits and toils of the Kazakhs are in most respects similar to those of the Kara-Kirghiz. Some of the wealthy steppe nomads own as many as 20,000 large fat-tailed sheep. Goats are kept mainly as guides for these flocks, and their horses are hardy and capable of covering from 50 to 60 miles at a stretch. Amongst the Kazakhs a few are skilled in silver, copper and iron work, which are the chief arts besides skin dressing, wool spinning and dyeing, and carpet and felt weaving. However, trade mainly consists of exchanging their livestock for woven and other goods from Russia, China and Turkestan.

contact

contact +44 20 7313 8040

+44 20 7313 8040