ames Digman Wingfield

(British 1800 - 1872)

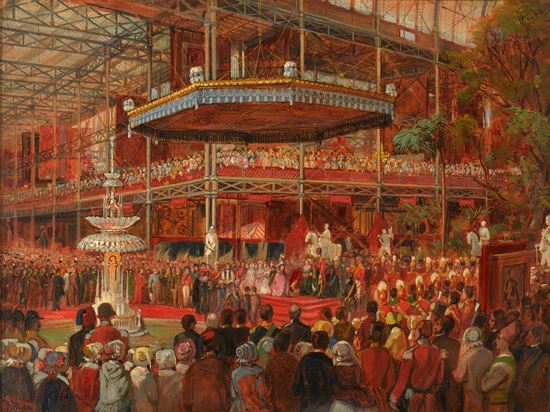

The Opening of the Great Exhibition

signed, inscribed and dated ‘Sketch J D Wingfield/MAY 1851’ (lower left)

oil on paper laid down on board

36 x 48 cm (14¼ x 19 in)

The present work is a study for the painting entitled The Opening Ceremony of the Great Exhibition, London, exhibited at the British Institution in 1852 (no. 414), and now in the collection of the Nottingham Castle Museum. There is also a second, smaller version in The Royal Collection, which was acquired by Queen Victoria (1819-1901), herself clearly visible in the present work.¹

‘The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations’ was held in Hyde Park in London from 1st May to 15th October 1851, within Sir Joseph Paxton’s (1803-1865) Crystal Palace. The Palace was created especially for the exhibition, which attracted seventeen thousand exhibitors from around the world and over six million visitors - almost one third of the entire population of Britain at the time. The Crystal Palace itself was almost outdone by the park in which it stood, which contained beautiful fountains and unrivalled collections of statues, many of which were copies of great works from around the world, and several of which are depicted in the present work.

In the present work James Digman Wingfield depicts the inauguration of the exhibition by Queen Victoria, who stands on a raised platform dressed in a pink gown. Around her are some of the most notable figures in British society, including Prince Albert (1819-1861), who was one of the principle organisers of the event, the aged Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) and the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Sumner (1780-1862), who had officiated over the religious aspects of the events. Beyond the Queen one can see the beginnings of the Indian section of the exhibition, but the details of the exhibits themselves are hard to discern. Instead it is the soaring majesty of Crystal Palace itself, and the throngs of people that are Wingfield’s focus. Twenty five thousand people visited the event, and as Hermione Hobhouse has said, ‘the success of the opening on 1 May has passed into legend’.² Wingfield successfully conveys the atmosphere of the eager and excited crowd, as they stand, jammed together, watching and listening to their monarch on this historic occasion. The artist was clearly greatly inspired by the exhibition; in addition the three works already discussed, there exists a sketch in the Courtauld Gallery, executed from one of the balconies, which provides a more panoramic view of the space.³

Wingfield was a British painter who specialised in painting portraits and architectural scenes. His work is of particular importance in terms of reconstructing historical events, for instance in his depiction of the Raphael cartoons at Hampton Court Palace. The cartoons were moved to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1865, yet Wingfield’s detailed work shows how the cartoons would have looked in situ before they were relocated.

¹ Royal Collection inventory no. 405569.

² Hobhouse, H., The Crystal Palace and the Great Exhibition: Art Science and Productive Industry, a History of the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, p.61.

³ Courtauld Gallery inventory no. D.1952.RW.3456.

with Thos. Agnew & Sons, 1987.

British Painting of Three Centuries, Thos. Agnew & Sons Ltd, 2 June - 24 July 1987, no. 29.

The present work is a study for the painting entitled The Opening Ceremony of the Great Exhibition, London, exhibited at the British Institution in 1852 (no. 414), and now in the collection of the Nottingham Castle Museum. There is also a second, smaller version in The Royal Collection, which was acquired by Queen Victoria (1819-1901), herself clearly visible in the present work.¹

‘The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations’ was held in Hyde Park in London from 1st May to 15th October 1851, within Sir Joseph Paxton’s (1803-1865) Crystal Palace. The Palace was created especially for the exhibition, which attracted seventeen thousand exhibitors from around the world and over six million visitors - almost one third of the entire population of Britain at the time. The Crystal Palace itself was almost outdone by the park in which it stood, which contained beautiful fountains and unrivalled collections of statues, many of which were copies of great works from around the world, and several of which are depicted in the present work.

In the present work James Digman Wingfield depicts the inauguration of the exhibition by Queen Victoria, who stands on a raised platform dressed in a pink gown. Around her are some of the most notable figures in British society, including Prince Albert (1819-1861), who was one of the principle organisers of the event, the aged Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) and the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Sumner (1780-1862), who had officiated over the religious aspects of the events. Beyond the Queen one can see the beginnings of the Indian section of the exhibition, but the details of the exhibits themselves are hard to discern. Instead it is the soaring majesty of Crystal Palace itself, and the throngs of people that are Wingfield’s focus. Twenty five thousand people visited the event, and as Hermione Hobhouse has said, ‘the success of the opening on 1 May has passed into legend’.² Wingfield successfully conveys the atmosphere of the eager and excited crowd, as they stand, jammed together, watching and listening to their monarch on this historic occasion. The artist was clearly greatly inspired by the exhibition; in addition the three works already discussed, there exists a sketch in the Courtauld Gallery, executed from one of the balconies, which provides a more panoramic view of the space.³

Wingfield was a British painter who specialised in painting portraits and architectural scenes. His work is of particular importance in terms of reconstructing historical events, for instance in his depiction of the Raphael cartoons at Hampton Court Palace. The cartoons were moved to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1865, yet Wingfield’s detailed work shows how the cartoons would have looked in situ before they were relocated.

¹ Royal Collection inventory no. 405569.

² Hobhouse, H., The Crystal Palace and the Great Exhibition: Art Science and Productive Industry, a History of the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, p.61.

³ Courtauld Gallery inventory no. D.1952.RW.3456.

with Thos. Agnew & Sons, 1987.

British Painting of Three Centuries, Thos. Agnew & Sons Ltd, 2 June - 24 July 1987, no. 29.

contact

contact +44 20 7313 8040

+44 20 7313 8040